Picture of Columbus Circle Roundabout in New York. Voted Best Roundabout in the World by the British Roundabout Appreciation Society in 2013

Time to Travel in Better Circles?

by Michael N. Plei, PE

Introduction

Ask a knowledgeable traffic engineer and she will tell you that modern roundabouts in general are safer [1], more efficient [2] , environmentally friendly and less costly to maintain compared to signaled or stop intersections. She will probably add that roundabouts reduce gas consumption, intersection noise and vehicle emissions, all while improving safety not only for drivers, but for pedestrians and cyclists too. She might even conclude with these benefits are well established in the professional community that research and design roads. [3]

Typical Single Lane Roundabout

These impressive benefits are produced by the roundabout’s unique design. In essence, the roundabout is circular one-way road in which traffic enters and exists only from the right (in the U.S.). This design lets traffic flow more continuously – albeit at a slower pace – through the intersection. With fewer stops and starts, traffic moves quicker through the roundabout intersection while using less gas – less gas also means fewer emissions. The roundabout’s lower speeds, no oncoming traffic and no left-hand turns drastically reduces the frequency and severity of accidents.

The efficiency claims of roundabouts even caught the attention of the MythBusters™. The documentary series ran their own tests (Crossroad Conundrums) to determine if roundabouts lived up to their efficiency reputation. The “myth” that a roundabout is a far more effective way to move cars through an intersection than the four-way stop signs used in the US was confirmed as true. [4]

Roundabouts Work Well, But Not Everywhere

Roundabouts are not for every intersection [5] . Location where roundabouts may not be the best solution include:

- Insufficient space to fit a properly sized roundabout.

- Steep grades that limit visibility or the required horizontal and vertical geometry.

- Locations within a coordinated traffic signal network, where the roundabout would disrupt the vehicle flows.

- Intersections with significant mismatch of traffic flow from the connecting roads.

Other areas where roundabouts are possible, but may require additional design considerations, signage or potential signals include:

- Presence of numerous bicycles or pedestrians.

- Presence of numerous disabled and blind users.

- Large number of long vehicles. These can be addressed through more generous dimensions. Consideration of road wear due to heavy loads constantly turning needs to be considered in the design of the roundabout. [6]

- Presence of fire stations or police stations, which take precedence.

- Rail crossings. Precautions are taken similar to other intersections.

However, for the right type of location, roundabouts provide numerous benefits over the traditional intersection.

Roundabouts in the United States — a problem of perception

We know how to build them. There are currently an estimated 3,200 modern roundabouts in this country [7] . The first two U.S. roundabouts were built in Summerlin, NV in 1990 and their numbers have increased such that at least one can be found in every state. Wisconsin seems to be leading the pack with 280 [8] .

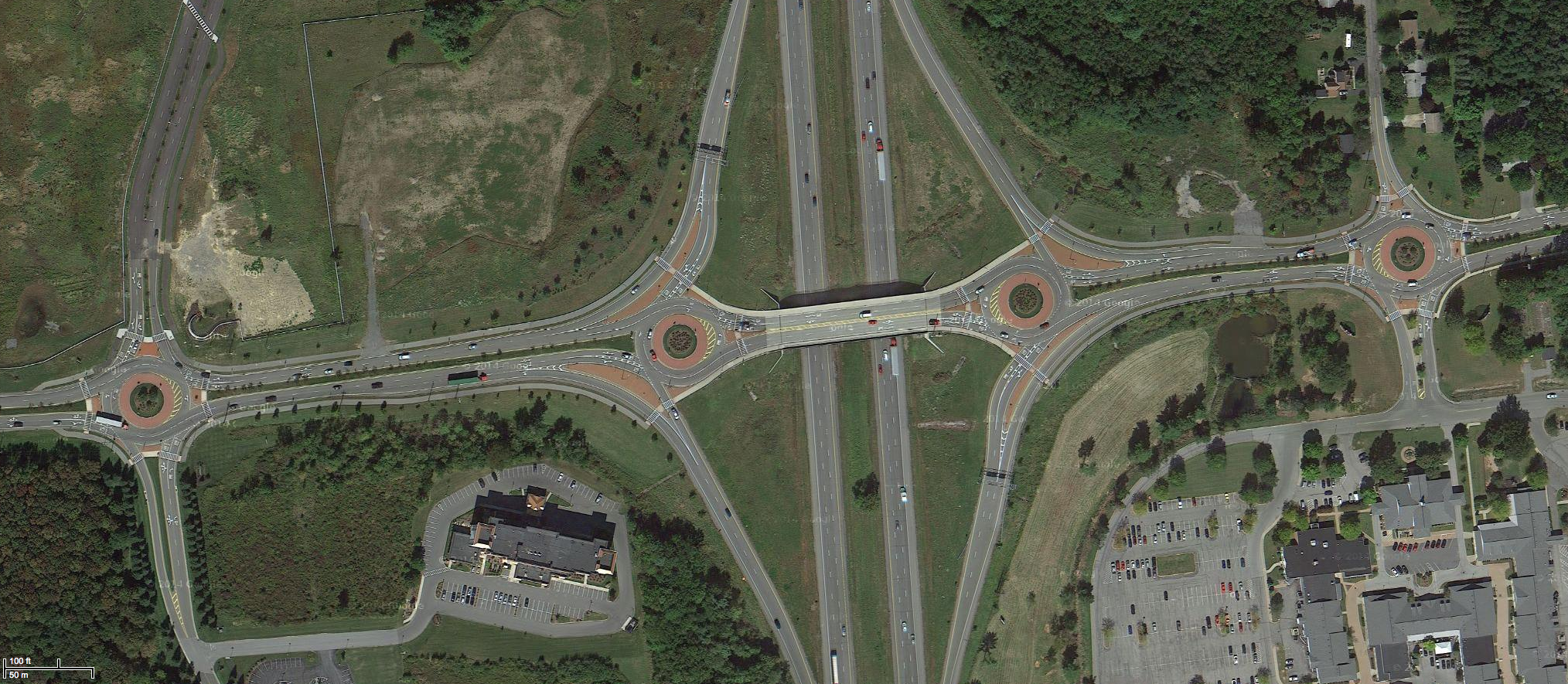

Some roundabouts are small, others are large and complex such as the Columbus roundabout in New York (shown at beginning of article), or these near Malta, NY (shown above).

Compared to the estimated 300,000 traffic intersections in the United States [9] , the number of roundabouts is only 1% of the traffic intersection number. When compared with the number of roundabouts worldwide — estimated at over 70,000 with France having at least 35,000 [10] ! – the U.S. seems far behind.

With all of their positive attributes, why aren’t roundabouts getting more love from U.S. drivers? One reason is that roundabouts take a little getting used to. An initial objection from American drivers is that roundabouts are confusing. While this can be a hurdle to adoption – at times echoed by local transportation officials – studies show that once people experience a roundabout their attitude changes toward acceptance [11] . This is a similar experience when right turn on red was first introduced.

In fact, some of the confusion about roundabouts play to its strength. The key to the roundabout is its ability to keep traffic moving in all directions, but at a slower speed than a traditional signaled intersection. The slower speeds and more awareness combine to help in reducing accidents.

Another hindrance is that many Americans have never encountered a modern roundabout. Some may remember its older (and troubled) cousin the traffic circle. Introduced in the United States in 1926, the circle fell out of favor with traffic engineers in the 1950’s. Many of these drivers would benefit from having a personal exposure to roundabouts.

Time to Move Forward

It is time that we make a concerted effort to use roundabouts in the US. While adoption continues the pace could be quickened with a little help from those in charge. I would recommend the following.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) should make a concerted effort to get states to build more roundabouts. The FHWA should use their power of the purse to help states see the benefits of roundabouts and make sure they are included as viable alternatives to intersections in all 50 states. In addition, the FHWA should help each state target areas in which a roundabout would make a significant impact on traffic flow and safety. Lastly, the FHWA should launch a marketing campaign in which roundabouts are actively shown to live up to the attributes that road engineers know that they have.

States need to pick up the ball and help get the word out about roundabouts. Many states spend time and effort to discuss roundabouts in the driver’s education programs, especially to new high school drivers. Other states should follow. Some states seem to take a minimal path in this regard for reasons that are difficult to ascertain. States should introduce their older drivers to the same level of roundabout understanding. A good opportunity to do this is during license renewal. Drivers should be asked relevant questions on their test about right-of-way and signage on roundabouts.

Those who design roundabouts and know them intimately should help get behind a joint private-public effort to share the positive (and negative) aspects of roundabouts. One of the most important avenues to achieve this is via social media. This media, coupled with short video that are mobile friendly, would make information about roundabouts easy share.

It’s time to increase the adoption of roundabouts in the US. Lives, money and time will be saved.

Notes

- ^ NCHRP Report 572 – Roundabouts in the United States, 2007

- ^ Roundabouts – Technical Summary, FHWA, Feb., 2010, Retrieved on August 6, 2014

- ^ Roundabouts - Q&A, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, retrieved on August 6, 2014

- ^ Crossroad Conundrums, Episode 222 “Traffic Tricks”, Mythbusters, July 22, 2013, retrieved on August 6, 2014

- ^ Modern Roundabout Practice in the United States, NCHRP Synthesis 264, 1998

- ^ Concrete Roundabouts, Luc Rens, EU Pave, see page 4, EU Pave Dec 2013

- ^ Status of Roundabouts in North America, Lee Rodegerdts, Kittelson & Associates, Inc., TRB 2014

- ^ (W)DOT Launches Ad Campaign To Teach Drivers About Roundabouts, Wisconsin Public Radio, retrieved on August 7, 2014

- ^ Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices - FAQ, Federal Highway Administration, retrieved on August 7, 2014

- ^ Les Mas Abico, Half the World’s Roundabouts are in France, retrieved on August 7, 2014

- ^ IIHS, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, Status Report, Vol. 36, No. 7, July 28, 2001