Fig. 1 Designer’s rendition of one of the Alameda / Paisano Roundabouts in El Paso, Texas.[1]

Roundabouts Built with CRCP

by Michael N. Plei, PE

Introduction

The number of roundabouts in the United States continue to grow as transportation departments and communities discover their many benefits. Better safety, greater traffic efficiency and lower operating costs are major points of attraction, but roundabouts can also create a sense of ambiance and community for those in the area.

A current estimate places the number of roundabout in the US at around 4,800 (as of December 2015). This is an increase of 50% from the end of 2013 estimate of 3,200.[2]

The impressive safety and efficiency benefits of roundabouts are due to its unique design. In short, the roundabout is circular one-way road in which traffic enters and exits only from the right (in the United States). This design lets traffic flow more continuously – albeit at a slower pace – through the intersection. With fewer stops and starts, traffic moves more quickly through the roundabout intersection while using less gas – less gas also means fewer emissions. With lower speeds, no oncoming traffic and no left-hand turns, roundabouts can drastically reduce the frequency and severity of accidents.

The Designer’s Challenge

A question does arise, however, regarding the use of roundabouts on roads with significant truck traffic—What is the best way to design a roundabout to accommodate large rigs with heavy loads?

Accommodating larger trucks on a roundabout can be addressed by properly sizing the number of lanes and deploying an inner apron. The apron keeps cars and small trucks off the inner circle, but allows larger trucks to use part of the inner area to navigate the curve.

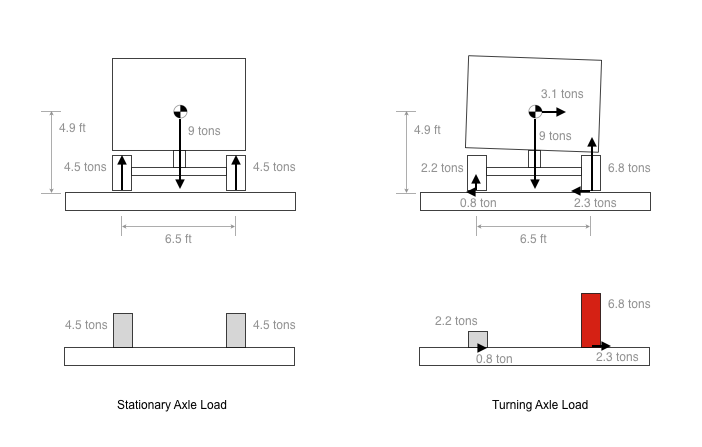

Another important issue to consider with heavy-load trucks is the additional forces these vehicles apply to the road and its surface. When a vehicle is stationary the forces on the road are composed of the weight of the truck as transmitted through the tires (see Fig 2., left side).

Fig. 2 Stationary and Moving Truck Loads

However when a vehicle is making a continuous turn, as on a roundabout, additional forces emerge. The turning generates centripetal forces. These forces create heavier wheel loads and additional tire friction on the road surface. For heavy-load trucks these additional loads can be significant (see Fig 2., right side).

Pavement Options

While many light traffic roundabouts are built with a flexible asphalt surface, this solution would not be adequate for those serving heavy-load trucks. These situations often lead designers to adopt concrete over a flexible pavement layer.

While a concrete pavement is the right choice for these types of roundabouts, there is a question as to what type of concrete pavement to use. Historically in the United States, that decision has defaulted to Jointed Plain Concrete Pavement (JPCP), a technology familiar to most transportation departments.

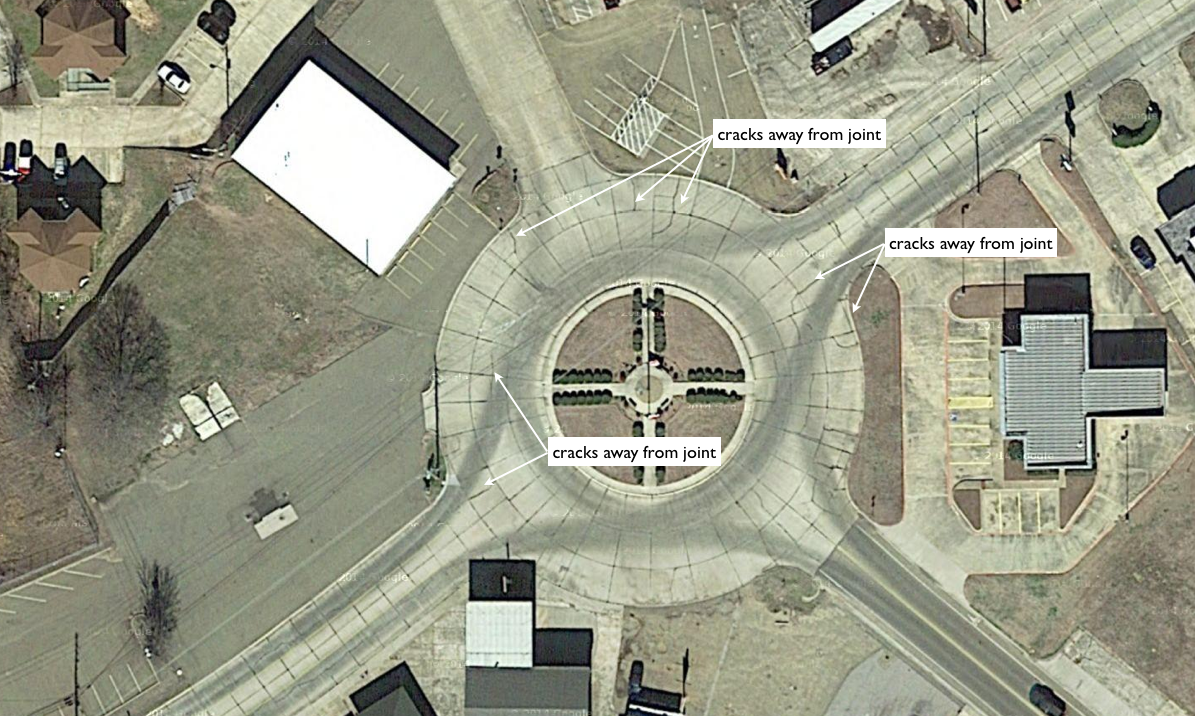

Fig. 3 Cracking in JPCP Roundabout – Redwater Rd, Wake, Texas.

However, certain issues can make JPCP roundabouts difficult to construct and maintain. The inherent form of the roundabout makes the layout of joints, sawcut timing and joint maintenance challenging — often more art than science (See Fig. 3).

Another concrete technology, Continuously Reinforced Concrete Pavement (CRCP), is specifically designed to control cracks and eliminated joints all together. CRCP has been used in many states — including Texas — and overseas for many years and has a reputation of being long lasting, reducing the need for maintenance.

TxDOT Approach

TxDOT has many years of experience using CRCP. Texas began using CRCP in 1951 and has nearly 14,000 lane-miles of CRCP in its inventory. In addition, TxDOT has a very active research effort focussed on increasing CRCP’s cost efficiency and overall performance. They are also increasing the use of CRCP as Texas expands its roadway network, as it has performed exceeding well in the state.

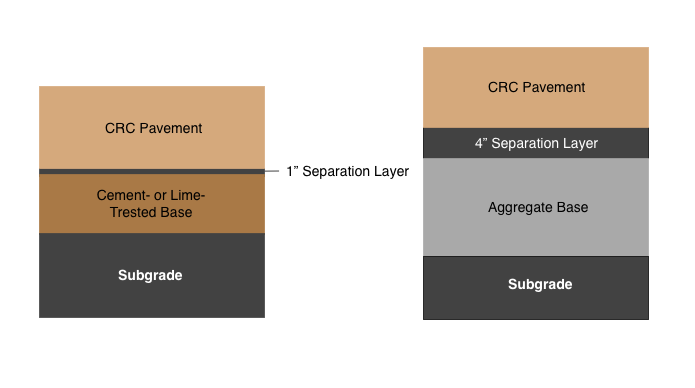

The following provides two samples of their CRCP pavement configurations.

Fig. 4 Example of TxDOT CRCP Pavement Design.

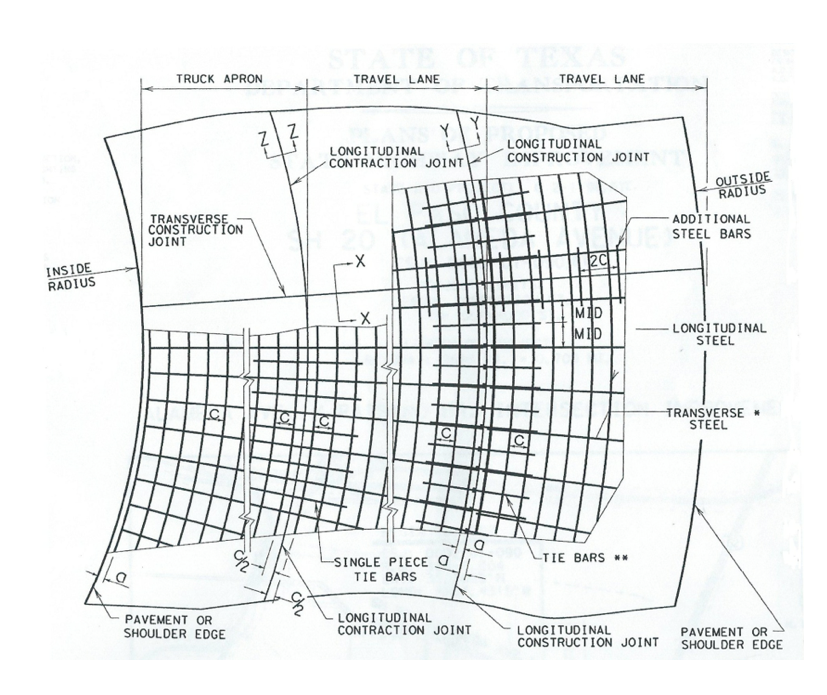

As depicted in "Fig. 5, TxDOT uses the following typical rebar pattern layout. As can be seen for the longitudinal steel bars – given the sizes of bars and radius of curvature used in roundabouts – there will be no problem in curving the bars to fit. The transverse steel bars simple follow the maximum spacing requirement at the outside radius of the pavement.

Fig. 5 Typical Radial Layout Pattern.

While Texas has been building roads with CRCP since the 1950's, using CRCP technology for building concrete roundabouts in the United States is relatively new. This is not the case in Europe. Belgium and The Netherlands have been building CRCP roundabouts since the 1990s, relying on this technology for heavily-trafficked, low-maintenance roadways. Belgium has constructed more than 50 roundabouts with CRCP since 1995.

US CRCP Roundabouts

The following roundabouts are the first modern roundabouts built in the US using CRCP technology.

Alameda-Paisano Roundabouts[3]

Fig. 6 Designer's rendition of the Alameda / Paisano Roundabouts in El Paso, Texas.

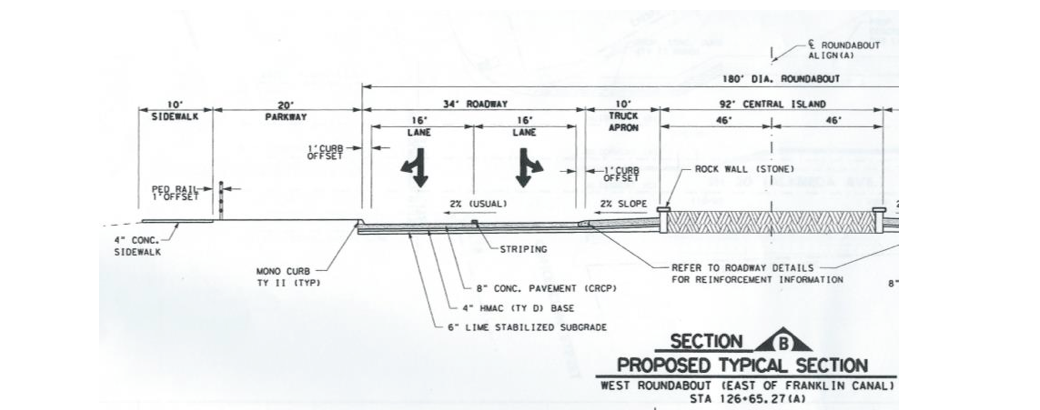

Technical Specifications:

- Inside Radius: 46'-0" (10" CRCP with #6 bar at 7" spacing = 0.63%).

- Intermediate Radius at Apron: 56'-0" (8" CRCP with #6 bar at 9" spacing = 0.61%).

- Outside Radius: 90'-0" (8" CRCP with #6 bar).

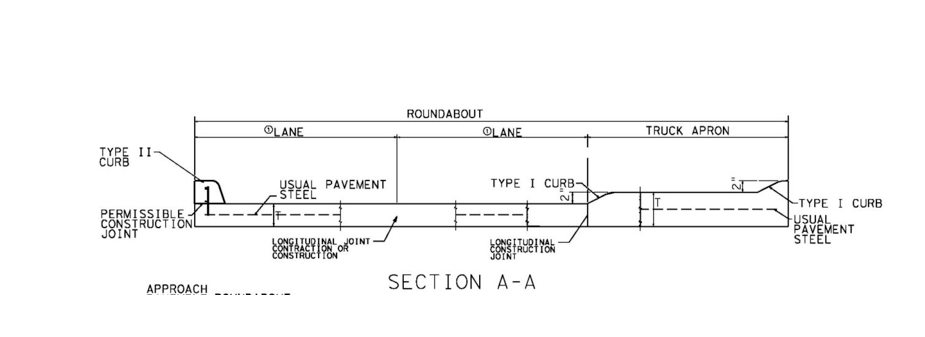

Fig. 7 Alameda - Paisano Roundabouts, El Paso, Cross Section View.

The truck apron allows big rigs to navigate into, around, and out of the roundabout by using the mountable curb, while keeping automobiles and smaller trucks on the main surface. The roundabout pavement is separated from the approaching roadway pavement by a joint. Location of the approaching pavement joints is dictated by the layout of the lanes and the curb return details.

FM-1375 Roundabouts[4]

Fig. 8 Images of FM-1375 Roundabouts in Walker County, Texas.

Roundabouts were used as a solution to reduce high-severity accidents that occur where a Farm-to-Market (FM) road intersects a highway frontage road. Both roadways typically allow high speed vehicle operations. Roundabouts require reduced speeds for navigation and provide good sight distances to see approaching vehicles.

Fig. 9 Construction Images of FM-1375 Roundabouts in Walker County, Texas.

Technical Specifications:

- Inside Radius: 51'-6" (9" CRCP with #6 bar at 6" spacing = 0.61%).

- Intermediate Radius at Apron: 65'-6" (7" CRCP with #5 bar at 6.5" spacing = 0.68%).

- Outside Radius: 89'-6" (7" CRCP with #5 bar).

Fig. 10 FM-1375 Roundabouts, Walker County, Cross Section View.

Summary

TxDOT has had proven success with building roads with CRCP since the 1950s. It is no surprise that the state agency has also chosen to build roundabouts with this proven technology.

CRCP provides a unique set of attributes to address the challenges of roundabouts that carry heavy-load trucks.

- Performs well over its design life.

- Long-lasting with minimal maintenance.

- Minimal jointing and saw cutting compared with alternative concrete choices.

- CRCP’s strength characteristics reduces pavement thickness.

- Eliminates rutting and shoving.

Given these inherent benefits, CRCP pavement is a good choice for roadways with significant truck traffic, and especially advantageous for heavy-load roundabouts.

Notes

- ^ Texas Department of Transportation – Alameda / Paisano Roundabouts, retrieved on January 26, 2016

- ^ Roundabouts USA – History, RoundaboutsUSA.com, Retrieved on January 27, 2016

- ^ Texas Department of Transportation – Alameda / Paisano Roundabouts, retrieved on January 26, 2016

- ^ Texas Department of Transportation – FM 1375 Roundabouts, retrieved on January 26, 2016